QT Prolongation: Medications That Raise Arrhythmia Risk

When a medication changes the way your heart beats - not in a good way - it can be deadly. QT prolongation is one of those silent dangers. It doesn’t cause symptoms until it’s too late. No chest pain. No dizziness. Just an elongated electrical signal on an ECG that can spiral into a fatal heart rhythm called torsades de pointes. And it’s not rare. More than 200 medications - from antibiotics to antidepressants - are known to cause it.

What Exactly Is QT Prolongation?

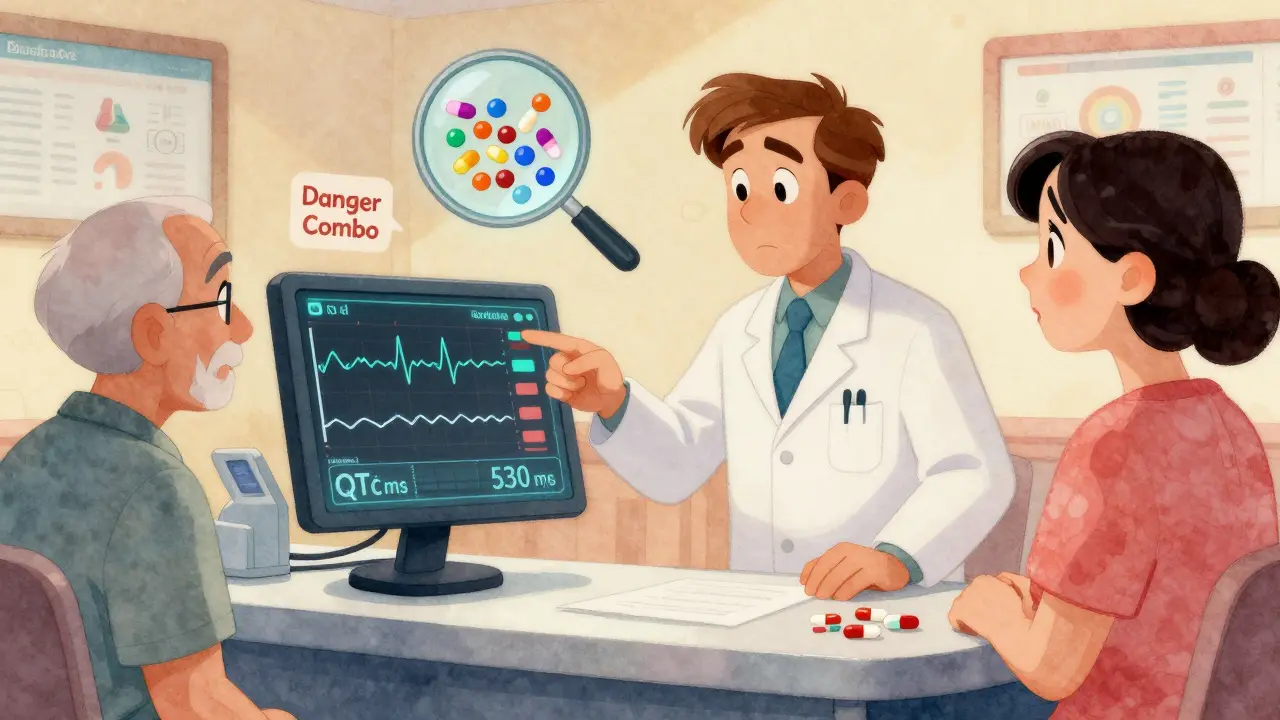

The QT interval on an ECG measures how long it takes your heart’s lower chambers (ventricles) to recharge after each beat. If that time stretches too long, the heart’s electrical system becomes unstable. That’s QT prolongation. It’s not a disease itself - it’s a warning sign. The longer the QT interval, especially when corrected for heart rate (called QTc), the higher the chance of a dangerous arrhythmia. The standard cutoff? A QTc over 500 milliseconds. Once you cross that line, your risk of torsades de pointes jumps 3 to 5 times. Even a rise of more than 60 ms from your baseline can be dangerous. And women are at higher risk - about 70% of documented cases occur in females, especially after childbirth.How Do Medications Cause This?

Most QT-prolonging drugs block a specific potassium channel in heart cells called hERG. This channel helps the heart reset after beating. When it’s blocked, the heart takes longer to recharge - and that delay can trigger chaotic rhythms. It’s not always intentional. Many of these drugs weren’t designed to affect the heart at all. Class III antiarrhythmics like sotalol and dofetilide are made to prolong the QT interval to stop abnormal rhythms. But they carry a paradox: they fix one problem while creating another. Sotalol, for example, causes torsades in 2-5% of patients. Amiodarone also prolongs QT, but its risk is lower (under 1%) because it blocks multiple channels, not just hERG. But here’s where it gets tricky: many everyday medications can do the same thing.High-Risk Medications You Might Be Taking

Some drugs are obvious risks. Others? Not so much.- Antibiotics: Erythromycin and clarithromycin can prolong QT by 15-25 ms. Azithromycin is lower risk, but still dangerous when combined with other QT-prolonging drugs.

- Antifungals: Fluconazole, especially at doses above 400 mg/day, increases QTc significantly.

- Antipsychotics: Haloperidol, ziprasidone, and thioridazine are high-risk. Ziprasidone carries a black box warning from the FDA for ventricular arrhythmias.

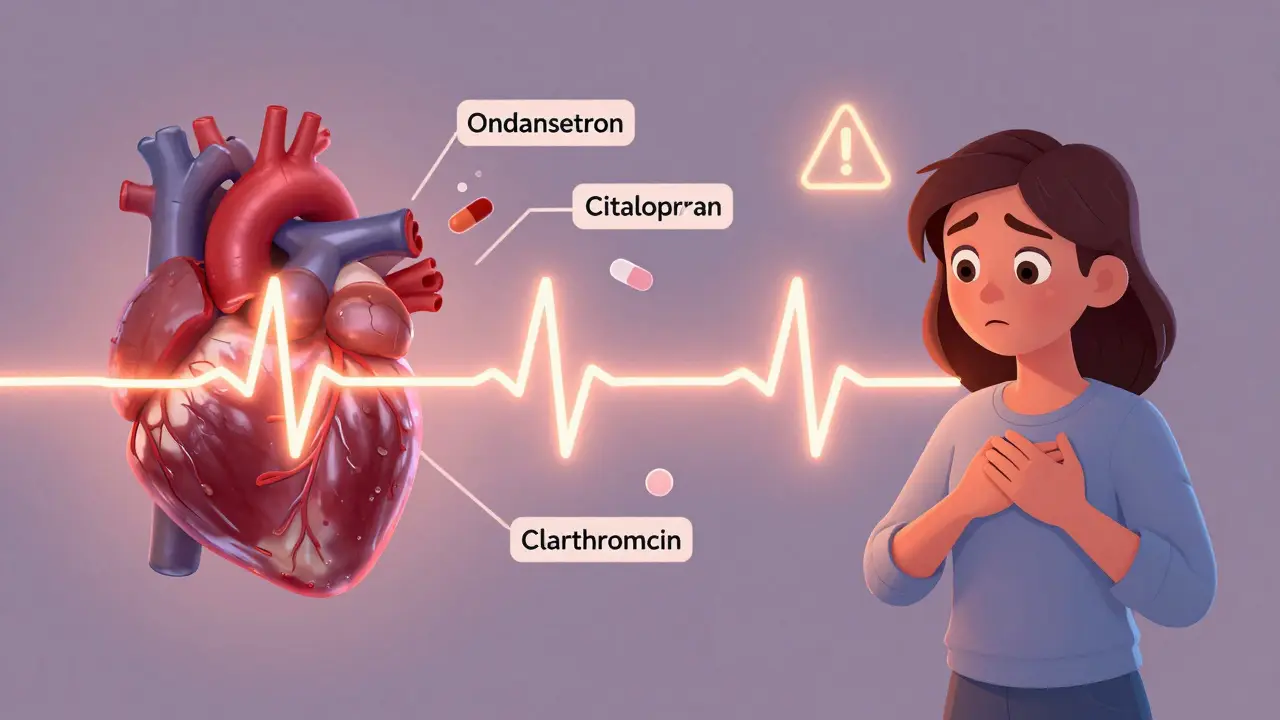

- Antiemetics: Ondansetron (Zofran), commonly given for nausea, is one of the most frequent culprits in real-world cases - involved in over 40% of reported torsades events.

- Antidepressants: Citalopram and escitalopram are dose-dependent. The FDA limits citalopram to 40 mg/day (20 mg if you’re over 60) because higher doses sharply increase QTc.

- Opioid replacement: Methadone is a major concern. Doses over 100 mg/day carry a clear risk of torsades. Many patients on maintenance therapy have QTc values above 470 ms - but with monitoring, most stay safe.

- Oncology drugs: Vandetanib, nilotinib, and sunitinib are among 12 out of 27 approved tyrosine kinase inhibitors with QT prolongation warnings.

It’s Not Just the Drug - It’s the Combo

The biggest danger isn’t one drug. It’s two or more together. A 2020 review of 147 torsades cases found that 68% involved multiple QT-prolonging medications. The average patient was taking 2.3 of them. Common dangerous pairs:- Ondansetron + azithromycin

- Haloperidol + ondansetron

- Citalopram + clarithromycin

Who’s Most at Risk?

It’s not just about the drug. Your body matters too.- Women: Hormonal differences make them more sensitive to hERG blockade. Postpartum women are especially vulnerable.

- Older adults: Kidney and liver function decline with age, slowing drug clearance. This leads to higher blood levels.

- People with heart disease: Scarred or weakened hearts are more prone to arrhythmias.

- Those with low potassium or magnesium: Electrolyte imbalances make the heart even more electrically unstable.

- People with genetic risk: About 30% of drug-induced torsades cases involve hidden mutations in hERG or related genes. You might not know you have it until a drug triggers it.

What Should You Do?

If you’re on any of these medications, here’s what actually works:- Get a baseline ECG before starting high-risk drugs - especially if you’re over 65, female, or taking more than one QT-prolonging med.

- Repeat the ECG within 3-7 days after starting or increasing the dose. That’s when drug levels peak and QTc changes are most likely.

- Check electrolytes. Low potassium or magnesium? Fix it before starting the drug.

- Know your combo risks. Ask your pharmacist: "Is this safe with my other meds?" Many don’t even know about QT prolongation.

- Don’t ignore symptoms. If you feel lightheaded, faint, or have palpitations after starting a new drug, get checked immediately.

What About Monitoring?

Some doctors argue that routine ECGs for low-risk drugs are unnecessary. After all, the chance of torsades with most non-cardiac drugs is less than 1 in 10,000 per year. But when it happens, it’s often fatal. And it’s preventable. The European Society of Cardiology and Medsafe (New Zealand) both recommend baseline and follow-up ECGs for high-risk patients. Hospitals using electronic alerts in their systems cut inappropriate prescribing by 58%. That’s not a small win.The Future: Safer Drugs and Better Tools

The pharmaceutical industry is changing. The FDA, EMA, and Japan’s PMDA launched the CiPA initiative in 2013 to move beyond just measuring QT intervals. Now, new drugs are tested on multiple ion channels and modeled in computer simulations before they even reach humans. Since 2016, about 22 drugs have been dropped from development because of proarrhythmia risk - a sign that safety is finally being taken seriously. In 2024, the FDA made CiPA mandatory for new drug applications. That means fewer dangerous drugs will reach the market. Meanwhile, AI is stepping in. A 2024 study showed an algorithm could predict torsades risk with 89% accuracy by analyzing tiny ECG waveform details that humans miss. Genetic testing is also advancing - researchers have found 23 gene variants that explain 18% of why some people are more vulnerable.Bottom Line

QT prolongation isn’t something you can feel. But it’s something you can prevent. If you’re prescribed a new medication - especially if you’re on others already - ask: "Could this affect my heart’s rhythm?" Get a simple ECG. Check your electrolytes. Avoid dangerous combos. Don’t assume your doctor knows every interaction. The data is clear: this risk is real, measurable, and preventable.One ECG, one conversation, one dose adjustment - that’s all it can take to stop a death before it starts.

What medications are most likely to cause QT prolongation?

The highest-risk medications include Class III antiarrhythmics like sotalol and dofetilide, antipsychotics like haloperidol and ziprasidone, antibiotics like erythromycin and clarithromycin, antiemetics like ondansetron, antidepressants like citalopram, and opioids like methadone. Over 220 drugs are currently listed on crediblemeds.org as having potential to cause torsades de pointes.

Is QT prolongation always dangerous?

Not always. A slight increase in QTc (under 500 ms and less than 60 ms from baseline) may not pose immediate risk, especially in healthy individuals. But when QTc exceeds 500 ms, or increases sharply from baseline, the risk of torsades de pointes rises dramatically - often by 3 to 5 times. The danger increases with other risk factors like age, gender, electrolyte imbalances, or multiple interacting drugs.

Why are women at higher risk for drug-induced torsades?

Women have longer baseline QT intervals than men, partly due to hormonal differences. Estrogen may enhance hERG channel blockade, while testosterone may have a protective effect. Studies show women account for about 70% of documented torsades cases, with the highest risk occurring in the postpartum period when hormone levels shift rapidly.

Can I take ondansetron if I’m on an antidepressant?

It depends. Ondansetron can prolong QT, and so can many antidepressants like citalopram or escitalopram. Combining them significantly increases risk. If you need an anti-nausea drug and are on a QT-prolonging antidepressant, ask your doctor about alternatives like metoclopramide (with caution) or non-drug options. If ondansetron is necessary, get an ECG before and within 3-7 days after use.

How often should I get an ECG if I’m on a QT-prolonging drug?

For high-risk medications - like sotalol, methadone, or ondansetron in combination with other drugs - get a baseline ECG before starting. Then repeat it 3 to 7 days after starting or after any dose increase. If your QTc stays under 500 ms and doesn’t increase more than 60 ms from baseline, you’re likely safe. Continue monitoring if you have other risk factors like kidney disease or low potassium.

Can I reverse QT prolongation if I stop the drug?

Yes, in most cases. Once the offending drug is stopped, the QT interval typically returns to normal within days to weeks, depending on the drug’s half-life. For example, QT prolongation from ondansetron usually resolves within 24-48 hours. For drugs like amiodarone or methadone, which have very long half-lives, it may take weeks or even months. Always follow up with your doctor - don’t assume it’s safe just because you feel fine.

Are there any safe alternatives to QT-prolonging drugs?

Yes, in many cases. For nausea, alternatives to ondansetron include metoclopramide (though it has its own risks) or non-pharmacological methods like ginger or acupressure. For depression, sertraline or bupropion carry lower QT risk than citalopram. For infections, azithromycin is lower risk than erythromycin. Always ask your doctor: "Is there a safer option?" There often is.