Retinal Vein Occlusion: Risk Factors and Injection Treatments

What Is Retinal Vein Occlusion?

Retinal vein occlusion (RVO) happens when a vein in the retina gets blocked, stopping blood from flowing out. This causes fluid and blood to leak into the retina, leading to swelling and vision loss. It’s not painful, but it can hit suddenly - one moment your vision is fine, the next it’s blurry or dark in part of your eye. There are two main types: central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO), which blocks the main vein, and branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO), which affects smaller branches. CRVO is more serious and often leads to worse vision loss. BRVO usually affects just a section of vision, like the top or bottom half of your sight.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Most people who get RVO are over 65. In fact, more than half of all cases happen in this age group. But it’s not just about getting older. The real danger comes from long-term health problems that damage blood vessels. High blood pressure is the biggest risk factor - present in up to 73% of people over 50 with CRVO. If your blood pressure isn’t controlled, your chances of RVO go up sharply.

Diabetes is another major player. About 10% of RVO patients over 50 have diabetes, and those who do tend to have worse outcomes. High cholesterol also plays a role. If your total cholesterol is above 6.5 mmol/L, your risk increases by about 35%. Glaucoma raises the risk too, especially if pressure inside the eye is high. Smoking adds to the problem - around one in three RVO patients are current or former smokers.

For younger people under 45, the causes are different. Oral birth control pills are the most common link in women. Blood disorders like polycythemia vera, leukemia, or inherited clotting conditions like factor V Leiden can also trigger RVO. These cases are rare, but they’re serious because they point to deeper health issues.

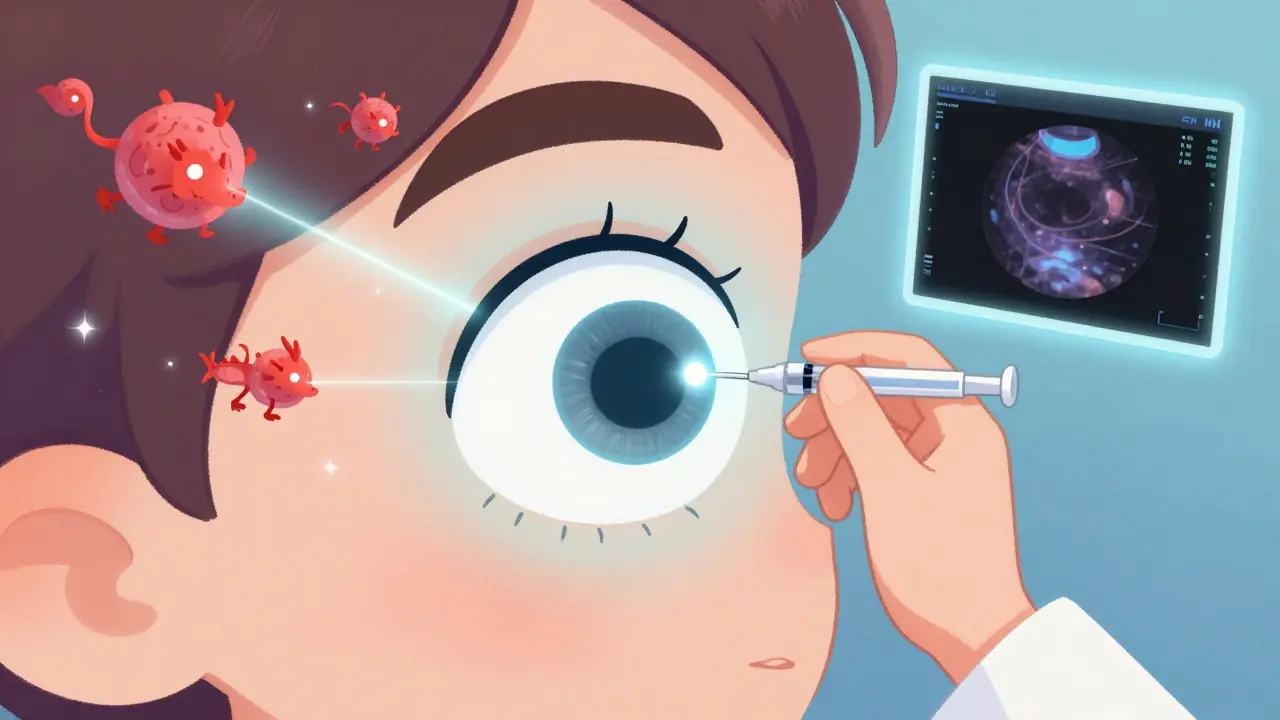

How Do Injections Help?

Injections into the eye are the main treatment for RVO - not to unblock the vein, but to treat the swelling (macular edema) that follows. The swelling is what blurs your vision. Two types of injections are used: anti-VEGF drugs and corticosteroids.

Anti-VEGF drugs - like ranibizumab (Lucentis), aflibercept (Eylea), and bevacizumab (Avastin) - block a protein called VEGF that causes leaking blood vessels. Clinical trials show these drugs can improve vision by 15 to 18 letters on an eye chart within six months. That’s the difference between barely reading a sign and reading it clearly. Aflibercept tends to work better in people with very poor starting vision, while ranibizumab and bevacizumab are effective for most.

Corticosteroid injections, like Ozurdex (dexamethasone implant), reduce inflammation and swelling too. They’re a good option if anti-VEGF drugs don’t work after several months. One study found 28% of CRVO patients gained 15 or more letters of vision after one Ozurdex implant. But there’s a catch: steroids often cause cataracts in 60-70% of patients who still have their natural lens, and can raise eye pressure, leading to glaucoma.

What’s the Treatment Routine Like?

Most doctors start with monthly anti-VEGF injections until the swelling goes down. That usually takes 3 to 6 months. Then, they switch to an as-needed schedule - you come in every few months for an OCT scan, which measures fluid in the retina. If the fluid comes back, you get another shot.

Real-world data shows patients need 8 to 12 injections in the first year. That’s a lot. Some people develop injection anxiety - the fear of the needle, the pressure, the unknown. Others struggle with cost. Bevacizumab costs about $50 per shot, while Lucentis and Eylea run $1,900-$2,000. Many clinics use bevacizumab because it’s safe and effective, even though it’s not officially approved for eye use.

There’s a new approach called treat-and-extend. You start with monthly shots, then stretch the time between them by 1-2 weeks each visit if your eye stays stable. A 2023 study showed this method gives the same results as monthly shots but cuts the number of visits by 30%.

What to Expect During the Procedure

The injection itself takes less than 10 minutes. Your eye is numbed with drops, cleaned with antiseptic, and held open with a tiny clip. The doctor uses a very fine needle to inject the medicine into the white part of your eye. You might feel pressure, but not pain. Afterward, you might see floaters or have a red spot on your eye - that’s normal. A small bleed under the surface of the eye happens in about one in four people.

Serious problems are rare. Endophthalmitis, a severe eye infection, occurs in fewer than 1 in 1,000 injections. Still, you should call your doctor right away if you have pain, worsening vision, or light sensitivity after the shot.

Long-Term Outlook and New Options

With treatment, about 30-40% of RVO patients regain vision good enough to read a newspaper (20/40 or better). Without treatment, most will lose vision permanently. That’s why sticking with the plan matters.

New treatments are coming. One is the Port Delivery System - a tiny refillable implant placed in the eye that slowly releases ranibizumab for months at a time. It’s already approved for macular degeneration and is being tested for RVO. Another is gene therapy, like RGX-314, which could let your eye make its own anti-VEGF medicine after a single injection. And there’s OPT-302, a new drug that blocks a different part of the VEGF system, being tested alongside Eylea for stubborn cases.

Doctors are moving toward personalized treatment. Your age, starting vision, other health conditions, and how your eye responds to the first few shots will determine whether you get anti-VEGF, steroids, or a mix. There’s no one-size-fits-all anymore.

What You Can Do to Lower Your Risk

Even if you’ve had RVO, you can reduce your chance of it happening again - or having it in the other eye. Control your blood pressure. Get your cholesterol checked. Manage diabetes if you have it. Quit smoking. Exercise regularly. Eat more vegetables, less processed food. See your eye doctor yearly, even if you feel fine. Early detection saves vision.

For younger people on birth control, talk to your doctor about alternatives if you have other risk factors. If you’ve had RVO under 45, ask for a blood test to check for clotting disorders. It could change your long-term care.

Living With RVO: The Real Challenges

It’s not just the shots. It’s the anxiety. The cost. The missed work. The fear that you’ll lose your independence. Many patients say the emotional toll is heavier than the physical one. Support groups help. Talking to others who’ve been through it makes a difference.

Don’t skip appointments because you’re overwhelmed. Vision can keep improving even after months of treatment. But if you stop, the swelling comes back - fast. Your doctor can help you find financial aid programs, sliding-scale clinics, or biosimilar drugs coming soon that will lower the price.

Retinal vein occlusion isn’t curable - yet. But it’s manageable. With the right treatment and support, most people keep enough vision to live independently, drive, read, and enjoy life.

Can retinal vein occlusion be cured?

No, RVO cannot be cured. The blocked vein doesn’t reopen. But the damage it causes - especially macular edema - can be treated effectively with injections. Most patients stabilize or improve their vision with ongoing treatment. The goal isn’t to reverse the blockage, but to prevent further vision loss and restore as much sight as possible.

How often do you need injections for RVO?

Most patients start with monthly injections for 3-6 months. After that, doctors switch to an as-needed schedule based on OCT scans. On average, people need 8-12 injections in the first year. Treat-and-extend protocols can reduce this by 30%, spacing shots further apart if the eye stays stable. Some patients eventually need only 2-4 shots per year.

Are eye injections painful?

No, they’re not painful. Numbing drops are used, and the needle is very thin. Most people feel pressure or a brief sensation, like a poke. The anxiety before the shot is usually worse than the procedure itself. The whole process takes under 10 minutes and is done in the doctor’s office.

What’s the difference between Lucentis, Eylea, and Avastin?

All three block VEGF and work well for RVO. Lucentis and Eylea are FDA-approved for eye use. Avastin was made for cancer but is used off-label for the eye because it’s much cheaper - about $50 vs. $2,000. Studies show they’re equally effective. Many clinics use Avastin, especially for patients with limited insurance. Eylea tends to work better for people with very poor starting vision.

Can RVO happen in both eyes?

Yes, but it’s uncommon. About 10-15% of people develop RVO in the other eye within five years. That’s why managing risk factors - like blood pressure, cholesterol, and diabetes - is so important. Regular eye exams help catch early signs before vision is lost.

Is there a new treatment on the horizon?

Yes. Gene therapies like RGX-314 aim to make your eye produce its own anti-VEGF medicine after one injection, potentially eliminating the need for repeated shots. A long-lasting implant called Susvimo, already approved for macular degeneration, is being tested for RVO and could reduce injections from monthly to quarterly. These are still in trials but show real promise for the next five years.

Next Steps if You’re Diagnosed

First, get a full eye exam - including OCT and fluorescein angiography - to confirm the type and severity of RVO. Ask your doctor about your baseline vision and what improvement you can realistically expect. Discuss whether you’re a candidate for anti-VEGF or steroid injections. Ask about cost options and financial assistance programs.

Next, manage your overall health. See your primary care doctor to get your blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar under control. If you’re under 45, ask about blood clotting tests. Quit smoking if you haven’t already.

Finally, stick with your treatment plan. Missed appointments lead to irreversible vision loss. If you’re overwhelmed, ask for help. Many clinics have patient navigators who can assist with scheduling, insurance, and emotional support. You’re not alone in this.

bro i got the Eylea shots last year 😭 honestly the anxiety before each one is worse than the needle. i cry every time but then i see my grandkids again and it’s worth it. 🥲💉

This is why you idiots don’t take care of your health. High BP? Diabetes? Smoking? You think the eye doctor is gonna fix your laziness? Get your shit together before you waste $2000 on a shot that won’t save your dumb ass.

I swear to god if I have to go through another one of these injections I’m moving to a cabin in the woods and living off berries. The pressure, the fear, the fact that I have to take off work and drive 45 minutes just to sit in a cold room while someone pokes my eyeball with a needle… I’m not a robot. I’m a person with trauma. 🥲

You know what’s really tragic? That we’ve reduced the miracle of human vision to a cost-benefit analysis on a spreadsheet. We’ve got gene therapy on the horizon, sure - but what about the soul of the patient? The quiet dread of waiting for the next injection? The way your hand trembles when you pick up the phone to schedule it? We treat the eye like a broken toaster, but the soul… the soul doesn’t have an OCT scan. It bleeds in silence. And no drug, no matter how expensive, can fix that.

Avastin? It’s not a bargain. It’s a testament to a system that values profit over person. And yet… I’m grateful for it. Because without it, I’d be blind. And that’s the cruel paradox of modern medicine: it saves you, but it reminds you daily that you’re a transaction.

Stop using Avastin. It’s illegal and dangerous. If you can’t afford Lucentis, don’t get the shot. Your vision isn’t worth breaking the law.

I just want to say thank you to the doctors and nurses who do these injections with so much care. I was terrified my first time, but my nurse held my hand and talked me through it. It’s not just medicine - it’s humanity. And for anyone struggling with the cost, there are patient assistance programs. Ask. You’d be surprised how many exist.

The pharmacokinetic profile of anti-VEGF agents in RVO is fundamentally heterogeneous due to inter-individual variability in VEGF-A isoform expression and ocular bioavailability. The current standard of care remains suboptimal given the absence of predictive biomarkers for treatment response. One must consider the cost-effectiveness threshold of Ozurdex in low-resource settings, particularly when confronted with the confounding variable of comorbid glaucoma.

I had CRVO in 2021. Got 11 injections. Now I read the news every morning. If you’re scared - you’re not alone. But skipping appointments? That’s the real loss. Please, don’t do it.

Bro in India we just call it 'eye block' and drink chai while waiting. The doc uses Avastin, charges 500 rupees, and we all laugh about how we’re basically guinea pigs. But hey - I can still see my daughter’s face. So yeah, I’ll take the chai and the needle.

I’m the author of the original post. Thank you all for sharing your stories. I didn’t expect this many people to relate so deeply. To the ones scared of the shots - I’ve been there. To the ones stressed about cost - I’ve sat in that waiting room too. To the ones who say ‘just get healthy’ - I get it. But sometimes, the body just breaks, no matter how hard you try. We’re not here to judge. We’re here to help each other see. Keep showing up. You’re doing better than you think.