Tiered Copays: Why Your Generic Copay May Be Higher Than Expected

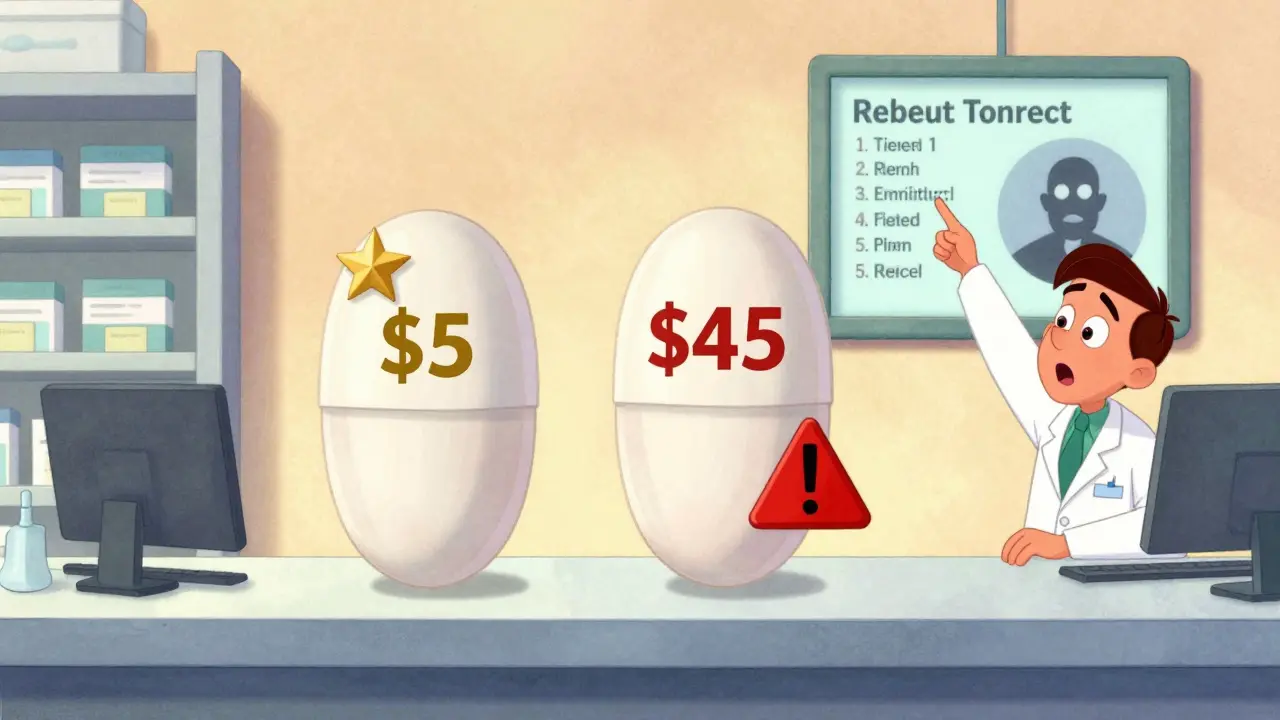

Ever picked up your prescription and been shocked that a generic drug cost more than you expected? You’re not alone. Many people assume that because a drug is generic, it should be the cheapest option on the table. But in today’s insurance system, that’s not always true. Some generic medications are placed in higher tiers - meaning you pay more out of pocket - even though they’re chemically identical to the cheaper version. This isn’t a mistake. It’s by design.

How tiered copays work

Most health plans today use a system called tiered copays. Instead of charging the same amount for every prescription, insurers divide drugs into tiers - usually four or five - and assign different prices to each. Think of it like a pricing ladder:- Tier 1: Preferred generics - lowest cost, often $0 to $15 for a 30-day supply.

- Tier 2: Preferred brand-name drugs - moderate cost, $25 to $50.

- Tier 3: Non-preferred brand-name drugs - higher cost, $60 to $100.

- Tier 4: Preferred specialty drugs - 20% to 25% coinsurance.

- Tier 5: Non-preferred specialty drugs - 30% to 40% coinsurance.

At first glance, this seems fair: cheaper drugs go in lower tiers, more expensive ones go higher. But here’s where it gets confusing: not all generics are in Tier 1. Some generics - even ones that work exactly the same as their cheaper counterparts - are stuck in Tier 2 or even Tier 3. And that’s why your $5 pill suddenly became a $45 pill.

Why a generic drug ends up in a higher tier

The biggest myth is that tier placement is based on how well a drug works. It’s not. A generic version of levothyroxine (used for thyroid conditions) or lisinopril (for high blood pressure) is chemically identical to any other generic of the same drug. There’s no clinical difference. So why the price jump?The answer lies in rebates. Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) - companies like CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx - negotiate deals with drug manufacturers. The manufacturer offers a discount (a rebate) to the PBM in exchange for the drug being placed in a lower tier. The more rebate, the lower the tier. If a generic drug’s manufacturer doesn’t offer a strong enough rebate, the PBM moves it to a higher tier - even if it’s the exact same medicine.

According to industry data, 68% of generic drugs moved to higher tiers between 2022 and 2024 were due to expired or reduced rebate agreements, not clinical reasons. That means your doctor prescribed a perfectly good generic, but your insurance didn’t get a good enough deal on it. So you pay more.

What about multiple generics?

Here’s another twist: sometimes there are multiple generic versions of the same drug. For example, there are over 20 different manufacturers of generic atorvastatin (Lipitor). Your plan might put one of them in Tier 1 - $5 copay - and another in Tier 2 - $20 copay. Both work the same. Both are FDA-approved. One just has a better rebate deal.Patients often don’t know this. They get their prescription filled, assume it’s the same, and are blindsided when the price changes. One Reddit user in May 2024 posted: "My levothyroxine generic went from $5 to $45 overnight. My doctor says they’re all the same. Why does my insurance care?" The answer? The PBM switched manufacturers and didn’t negotiate a rebate on the new one.

Specialty generics - the hidden cost trap

Even more confusing are specialty generics. These are generic versions of expensive biologic drugs - like adalimumab (Humira) or etanercept (Enbrel). These drugs treat serious conditions like rheumatoid arthritis or Crohn’s disease. The brand versions can cost $5,000 to $10,000 a month. The generics? Around $1,500 to $3,000.But here’s the catch: even though they’re cheaper than the brand, they’re still classified as specialty drugs. That means they fall into Tier 4 or 5 - and you pay 20% to 40% of the cost. For a $2,500 drug, that’s $500 to $1,000 out of pocket per month. That’s more than most people pay for a brand-name drug.

And unlike regular generics, these can’t be swapped out easily. They require special handling, storage, and often prior authorization. Patients on these drugs often don’t realize they’re paying coinsurance - not a flat copay - until they get the bill.

What you can do about it

You can’t change the tier system. But you can work within it.- Check your formulary - every plan updates it once a year, usually in October. Log in to your insurer’s website and search for your drug. Look for "preferred" vs. "non-preferred" labels.

- Ask your pharmacist - they know which generics are in which tier. If your drug jumped in price, ask: "Is there another generic version that’s cheaper?" Often, there is.

- Request a therapeutic interchange - if your doctor agrees, they can submit a form to your insurer asking to switch you to a lower-tier drug. This works 63% of the time, according to the Medicare Rights Center.

- Use cost tools - GoodRx, SmithRx, and your insurer’s own drug lookup tool (like Humana’s) show real-time copays across pharmacies. Sometimes, paying cash is cheaper than using insurance.

- Check for manufacturer assistance - many drugmakers offer coupons or patient assistance programs. For specialty generics, these can cover 20% to 50% of the cost.

One patient in Melbourne reduced her monthly cost from $140 to $25 after her pharmacist found a different generic version of her blood pressure medication that was still in Tier 1. She didn’t change her treatment. She just changed which version she got.

Why the system stays this way

Tiered copays were created to lower overall drug spending. Studies from the early 2000s show they worked: when non-preferred brands moved to higher tiers, demand dropped by over 15%. But the trade-off was complexity - and confusion.Insurers argue it keeps premiums low. But for patients, it feels arbitrary. A 2023 survey found 41% of insured adults had experienced a generic drug suddenly costing more, and 68% said insurers gave no clear explanation.

Regulators are starting to pay attention. The Inflation Reduction Act, effective in 2025, will cap out-of-pocket drug costs at $2,000 per year for Medicare Part D plans. But it doesn’t change tier structures. PBMs still control which drugs go where. And as specialty drugs keep rising - now making up 56% of total drug spending - the pressure to tier even generics will only grow.

What’s next

By 2026, experts predict the number of tiers will shrink from five to four on average. But the core problem remains: your generic drug’s price isn’t based on how well it works - it’s based on how much money the PBM got from the manufacturer.Until that changes, patients will keep getting surprised. The best defense? Stay informed. Know your plan. Ask questions. And never assume a generic is cheap just because it’s generic.

Why is my generic drug more expensive than the brand-name version?

It’s rare, but it can happen. Some brand-name drugs are in lower tiers because the manufacturer pays a large rebate to the Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM). Meanwhile, the generic version may be in a higher tier if its manufacturer didn’t negotiate a strong rebate. This is purely a business deal - not a reflection of the drug’s quality or effectiveness.

Can I switch to a cheaper generic version of my medication?

Yes - but you need to talk to your doctor and pharmacist. Many drugs have multiple generic manufacturers. Your pharmacist can check which one is in the lowest tier and ask your doctor if you can switch. In most cases, it’s a simple substitution with no clinical impact. About 63% of these requests are approved by insurers.

Why did my copay suddenly go up mid-year?

Insurance plans can change their formularies at any time - though most updates happen in October. A drug might move to a higher tier if the manufacturer’s rebate deal expired or was reduced. You’ll usually get a notice in the mail or via your online portal. If you’re affected, you can file an exception request with your insurer.

Are there any generic drugs that always cost more?

Yes - specialty generics. These are generic versions of very expensive biologic drugs (like Humira or Enbrel). Even though they’re cheaper than the brand, they’re still classified as specialty drugs and require coinsurance (20%-40%). These often cost hundreds or thousands per month, even with insurance.

Can I pay cash instead of using insurance?

Sometimes, yes. If your drug is in a high tier, using GoodRx or another discount service might cost less than your insurance copay. This is especially true for older generics. Always compare prices - your pharmacy can check both options for you.

Understanding tiered copays isn’t about memorizing rules. It’s about knowing that your drug’s price is tied to a contract between your insurer and a middleman - not your doctor’s prescription. The system isn’t broken. It’s just not designed to make sense to patients. The key is to ask, compare, and never accept the first price without checking if there’s a better option.